China is rapidly constructing what it aims to become the largest national park system in the world, an ambitious project that could redefine the global approach to conservation. With a target of 49 national parks spanning 272 million acres by 2035—an area larger than Texas and three times the size of the U.S. National Park System—China is positioning itself as a future leader in environmental protection and eco-tourism.

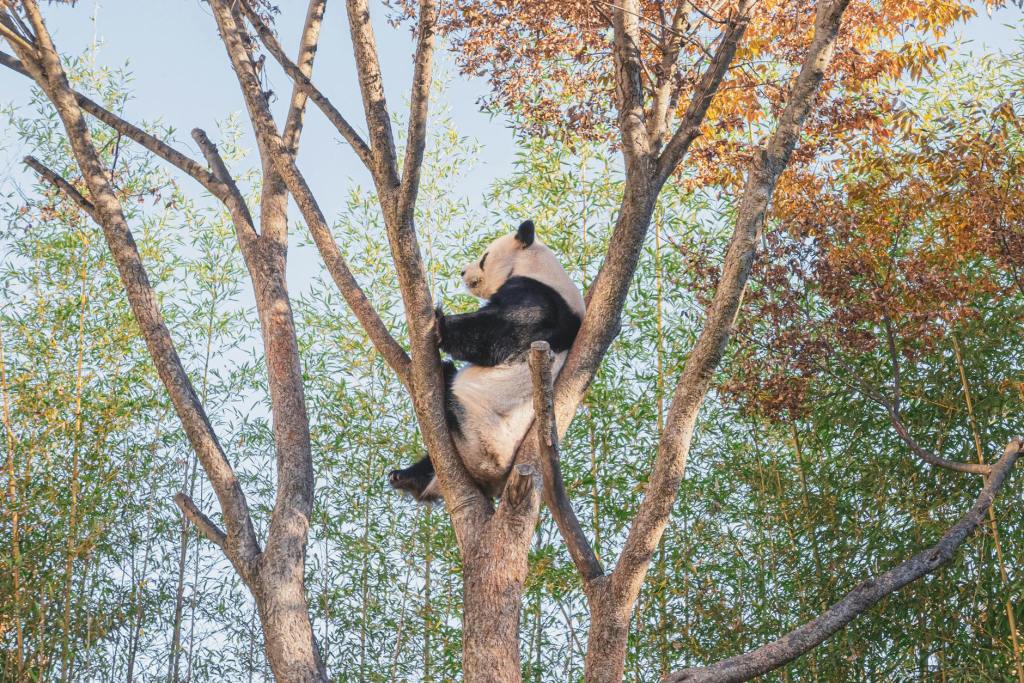

The initiative began only four years ago when China officially launched its first national park, marking a significant shift from its previous reliance on nature reserves, which often lacked international conservation standards. Since then, five national parks have opened, collectively covering 57 million acres. These parks span diverse ecosystems, from glaciated mountain ranges and tropical rainforests to high-altitude wetlands and vast desert landscapes. They provide refuge for endangered species such as the giant panda, Siberian tiger, Amur leopard, and Asian elephant.

This national park initiative represents more than environmental stewardship—it reflects a broader shift in China’s national priorities. In addition to ecological preservation, the parks are intended to promote cultural heritage, economic development, and public education. The integration of conservation with local community involvement and sustainable tourism offers a modern model of park management.

Unlike older park systems that sometimes relied on displacing local populations to create “pristine” wilderness areas, China’s strategy seeks to harmonize human presence with natural conservation. New policies are designed to prevent forced resettlement while ensuring that local communities benefit from tourism and conservation employment. These changes are a direct response to international criticism of past conservation models and a conscious effort to implement a more equitable and ecologically effective system.

China’s national parks are not merely expanded versions of its earlier nature reserves. Instead, they meet rigorous international standards set by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which require that such parks prioritize conservation above all else, limit tourism, and prohibit permanent residential housing within protected zones. These rules are strictly enforced to safeguard fragile ecosystems and support biodiversity.

This shift in conservation policy has already shown measurable results. Since the establishment of the new parks, populations of over 200 rare animal species and 100 endangered plant species have reportedly increased. These successes are attributed to stronger protection of critical habitats, more focused management, and the reduction of human interference.

The conservation zones also serve as crucial ecological buffers—designated areas that support biodiversity, act as climate regulation zones, and protect against soil erosion and desertification. They are essential for the long-term survival of many iconic and endangered species, and provide China with what scientists describe as “ecological security barriers.”

Culturally, the national parks system also helps preserve some of China’s oldest villages, traditional lifestyles, and historic relics. Many of the parks include areas of archaeological or spiritual importance, ensuring that national identity and history remain intertwined with the natural landscape. In this way, the park system does not just conserve ecosystems—it protects cultural legacies.

Economically, the national parks are emerging as a new engine of rural development. Infrastructure investments in remote areas are creating jobs, improving transportation, and attracting domestic tourists. Although most international visitors still focus on China’s major cities, tourism experts expect that as the parks expand and gain visibility, more foreign travelers will be drawn to the country’s diverse and often underappreciated natural beauty.

Public education is another key pillar of the project. Park programs aim to raise awareness about environmental protection, sustainability, and China’s rich biodiversity. By positioning national parks as outdoor classrooms, the government hopes to cultivate a deeper environmental consciousness among citizens, particularly younger generations.

This transformation comes as part of a larger trend in China’s development—one that sees environmental sustainability as critical to national progress. Known for large-scale infrastructure projects like the Three Gorges Dam and the high-speed rail network, China is now directing its immense capabilities and resources toward environmental regeneration.

Despite its late start compared to countries like the United States, China’s national park strategy benefits from hindsight. By learning from past mistakes and global best practices, the system is being designed from the ground up with flexibility, adaptability, and sustainability in mind.

In a world increasingly threatened by climate change and habitat loss, China’s national park initiative is not just an internal effort—it is a global statement. If successful, it could set a new standard for conservation and prove that rapid economic growth and large-scale environmental protection are not mutually exclusive. As the country continues to build what may become the world’s most expansive and ecologically significant park network, it offers a new vision for the future of wilderness preservation—one that merges culture, conservation, and community into a unified national mission.

Leave a comment